The Old Guard Retakes Control in Vietnam

Reform-minded Prime Minister Dung is on his way out.

Bruce Einhorn  January 29, 2016

January 29, 2016

Photographer: Maika Elan/Bloomberg

Dung’s defeat was a victory for Party General Secretary Nguyen Phu Trong, who leads an old guard schooled in the ways of a command economy. If this faction puts the brakes on liberalization, it could jeopardize Vietnam’s momentum. “They’re not going to reverse reforms, but they are not going to speed them up either,” says Zachary Abuza, a professor at the National War College in Washington. “They will be more cautious about the pace.”

Vietnam’s economy grew 6.7 percent last year, and will maintain that pace in 2016, according to analysts surveyed by Bloomberg. Foreign direct investment reached a record $14.5 billion in 2015, thanks to companies such as Samsung and LG that have made Vietnam a hub for manufacturing smartphones and TVs. Electronics now account for almost 30 percent of total shipments abroad, up from 18 percent in 2012. In December, Standard & Poor’s said Vietnam “could be the next Tiger economy.”

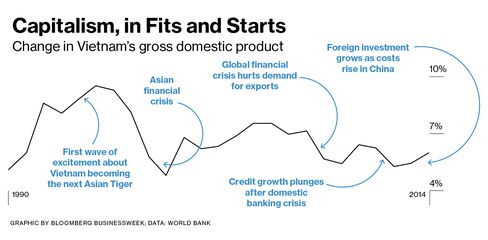

This isn’t the first time Vietnam has been heralded as the new Asian dynamo. The country’s journey to a socialist-oriented market economy, begun in 1986, has been bumpy. Inflation peaked at an annualized 23 percent in August 2011; last year alone, the government devalued the currency, the dong, three times. The nation is also prone to credit-fueled bubbles. Nonperforming loans hit a high of 17 percent of total bank lending in 2012 and remain a drag on growth.

Given that history, there are reasons for concern that policymakers won’t be able to keep the economy from overheating again. Plunging oil prices have spurred domestic consumption, but, because Vietnam’s crude exports generate about 10 percent of government revenue, the drop is doing little to bring down the budget deficit. The Vietnam Institute for Economic and Policy Research, a part of the national university, estimates the shortfall has reached 7 percent of gross domestic product. “I don’t think they’ve really solved the boom-and-bust cycle,” says Andrew Wood, head of Asia country risk for BMI Research in Singapore.

There’s still cause for optimism. Some manufacturers are shifting production from China to Vietnam to take advantage of the country’s ample workforce and lower wages. The World Bank projects Vietnam’s working-age population will expand 6.5 percent from 2015 to 2030, while China’s will decline 3 percent over the same period.

Vietnam’s share of all U.S. footwear imports by dollar increased to 13.9 percent in 2014, from 10 percent in 2012, according to the International Trade Commission. That came largely at China’s expense.

The country’s more than 90 million consumers, many of them young—60 percent of the population is under 35—are another draw for foreign companies. In December, Thai brewer Singha announced it was spending $1.1 billion to buy stakes in two subsidiaries of Vietnam’s largest listed consumer company, Masan Group. ANA, owner of Japan’s All Nippon Airways, in January said it will pay $108 million for 8.8 percent of Vietnam Airlines.

The tempo of dealmaking could pick up if Dung’s successor carries on with reforms. In December the government identified 18 industries that are open to foreign investment, including construction, manufacturing, property, and transport. The five-year development plan approved at the latest party congress calls for strengthening the private sector by guaranteeing businesses equal access to credit, land, and other resources enjoyed by state-owned enterprises. State-run companies tap 60 percent of the country’s bank loans while contributing just a third of GDP, according to government data. Nguyen Hieu, chief executive officer of a Hanoi construction company, who says he tried in vain last year to persuade banks to lend him $800,000 for a project, says he’s cautiously optimistic: “It’s good they recognize the importance of the private sector, but implementation is key.” Justin Kendrick, chief investment officer of Javelin Wealth Management in Singapore, cautions business leaders and investors to be patient. “Vietnam,” he says, “never achieves things at the pace people want.”

—With John Boudreau and Nguyen Dieu Tu Uyen

The bottom line: Vietnam’s market opening may slow with the ascendancy of a more conservative faction of the Communist Party.

http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-01-28/vietnam-s-old-guard-retakes-control

Không có nhận xét nào:

Đăng nhận xét